When we approached the Flores & Prats firm, we wanted to focus on their precise drawing just as much as their detailed mock-ups. We wanted to see a project that not only "values the time invested and accumulated in it but also sees said time as a virtue and not a defect;" an indication of paying attention to the process as well as the unexpected. (In this sense, it reminds me of reading about how to draw a forest, among other things, in "Las tardes de dibujo en el estudio Miralles & Pinós").

We conducted a long-distance interview with the Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores studio for this reason; to get a better idea of their thoughts on the impact of drawing on architectural representation.Their input makes clear the "why" of their decisions, and explains not only how they operate in a contemporary context but also indicates their relationship with construction among other disciplines.

Fabián Dejtiar: What inspired you to follow this path of architectural representation?

Flores & Prats: We started with Enric Miralles and later began our own studio. We emphasized drawing as a discipline that allowed us to incorporate multiple dimensions of a project into one blueprint. Blue-prints are the focal point of the studio and allow us to connect models with other works. In that way, drawing brings forth other ideas and even creates its own materials in the building process.

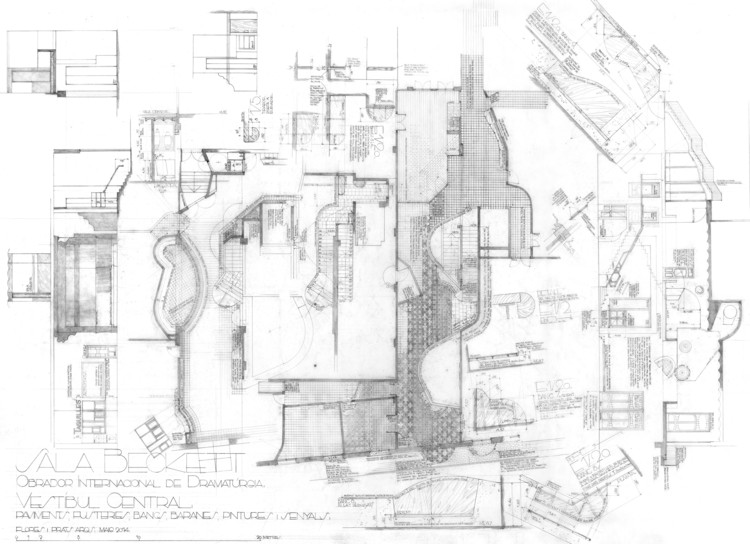

Through our work on older buildings like the Sala Beckett, the Casal Balaguer, and the Museo de los Molinos , we've been able to apply drawing as a tool for observation and time-keeping, allowing us to capture different time periods in one blue-print, forcing them to coexist. Transforming certain things into others, drawings and the models that come from them allow us, not a glimpse of what existed before and what came after, but rather a continuous idea that moves fluidly through time and space, transcending any barriers that lay before it.

On the other hand, projects with a lot of outside input, like the Pius XII Plaza or the Edificio 111, were occasions where a variety of opinions had to be put onto a single blue-print. With this type of project, which favors an architect that can incorporate diverse opinions and expertise, drawing out each idea allowed us to fit every contribution onto one page.

In our academic work, in Barcelona as well as other universities, drawing by hand is a way to expand an idea while also showing it to others. Because of this, the students' desks are identical to the ones in our own studio, where drawing leaves room for doubt and exposes the challenges of completing a design; however, being able to see the challenges is exactly what allows the designer to advance in their work.

FD: Enric Miralles...

F&P: Our time in his studio was a learning experience (Eva Prats worked with Carme Pinós and Enric Miralles from 1985 to 1990 and with Enric Miralles from 1991 to 1994. Ricardo Flores worked with Enric Miralles from 1993 to 1998). We spent hours drawing, first with pencil and then with ink. Over the years, drawing turned into actual designing. Even though it seemed our work was done with great liberty and spontaneity, it was actually the result of a slow and meticulous process. From this, we learned to precisely draw out incomplete ideas, which proved extremely useful in moving projects along. To this day, it's a discipline at the center of our work, school, and studio.

FD: How do you make this work in today's fast-moving environment, especially considering the pace at which architects are expected to work?

F&P: We don't rush ourselves in spite of the pace and demands of our field. It's a matter of bringing something fresh and new to every project and not presenting a project until it's got something good to offer.

We believe in time as another factor that improves and expands solutions. It allows us to take on clients, risk, and other experiences that tend to come about in a project. For that reason, we try to make time for developing projects beyond the given deadlines of the assignment, stretching out the time between the project's first sketches and its completion in order to give us a platform to research and test out different interests along the way. This allows us to see the process as a valuable material in itself, one capable of explaining the project as a whole.

FD: Would you consider your sketches as a design/project in themselves?

F&P: Many times we formulate sketches that can fully explain an aspect of the project. We identify an element of the project that interests us and which can function as an independent factor. This way of seeing projects, identifying concepts and ideas that come from within them, allows us to recognize issues that appear and re-appear in a different form, scale, or function.

However, these sketches, like the ideas they produce, are fragmented and unfinished by necessity. The difficulty is hitting the brakes on an idea and putting the pen down when it starts to distance itself from your initial goal.

FD: How do you make the transition from drawing to actually constructing your design?

F&P: We draw with the responsibility of building what we put onto paper. The sketch is a way to communicate through all phases of the project. First, you communicate observations and intentions, but this of course changes as the scale and construction materials are added to the mix.

We draw with the responsibility to build.

This is when a sketch becomes a letter to the construction team and, in it, our ideas are presented in a complete and concrete form. Precisely defining the geometry of a project is fundamental and patient work, most of which happens totally in the studio. By sticking geometric rules, we reduce the likelihood of intervention and misinterpretation by the construction team. With these sketches, we reiterate our ideas on the project. We lay out cords, rulers, triangles, and compasses in order to draw out the project with the same precision that we use while working at our desks. These sketches bring into focus the project imagined in the studio. The tools used for measuring the project under construction are the same ones we use in the studio.

FD: Any recommendations for anyone looking to set their own path? For the new generations of architects that work more with digital tools?

F&P: We encourage everyone to not totally abandon working by hand. The hand can follow and draw your imagination, while the AutoCad is technical and asks for measurements. Drawing by hand is much more fluid. The hand follows your thoughts as they come. Sometimes you get a different idea and the hand jumps to follow. This helps you: you can get distracted and start to draw other facets of the project. The hand follows, no questions asked, allowing the unexpected to easily appear.

In both the classroom and the studio we speak a lot about drawing by hand's ability to allow time to participate in what we are drawing. But this is only possible through a project that values ineffectiveness and built up time as a quality, not a defect. We're not interested in the speed and efficacy, especially not during the years of university training. Rather, we want to incorporate doubt, uncertainty, and risk into the creative process. Taking time to sketch by hand makes our thoughts and diverse interests visible on paper.

With the students, we spend the entire year sketching and drawing, looking to everything from old cartography to the reality on the streets, documenting written information and putting it into a sketch...drawing is our language throughout the course and it's all done by hand. It works better for us as a way to communicate and to have sessions in the classroom where we can see what's happening at the desks: the large sheets of paper are more public than any computer screen. Doubts are on display and the difficult points are filled in with graphite.